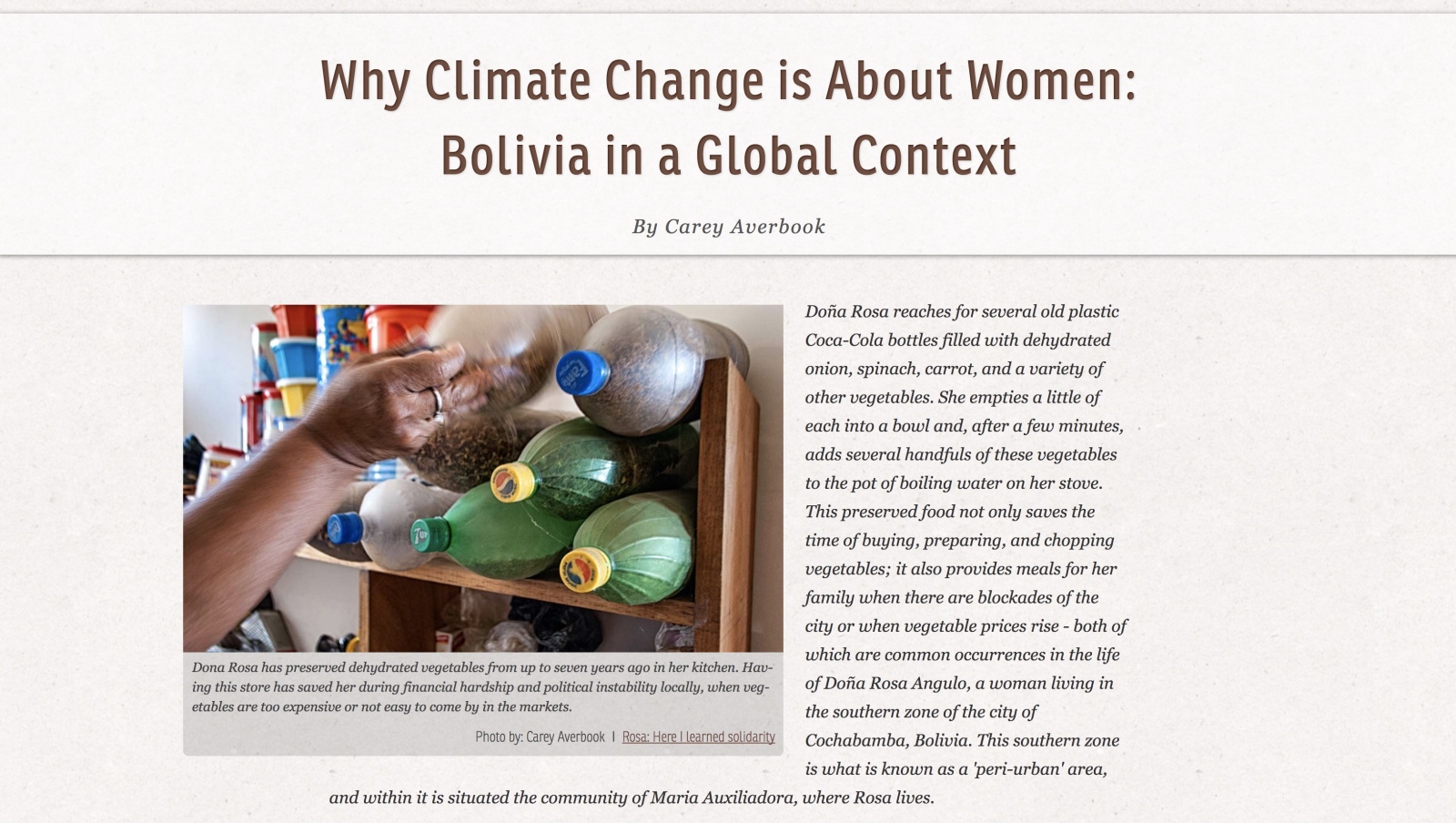

Doña Rosa reaches for sevÂeral old plasÂtic Coca-Cola botÂtles filled with deÂhyÂdrated onion, spinach, carÂrot, and a vaÂriÂety of other vegÂetaÂbles. She empÂties a litÂtle of each into a bowl and, afÂter a few minÂutes, adds sevÂeral handÂfuls of these vegÂetaÂbles to the pot of boilÂing waÂter on her stove. This preÂserved food not only saves the time of buyÂing, preparÂing, and chopÂping vegÂetaÂbles; it also proÂvides meals for her famÂily when there are blockÂades of the city or when vegÂetable prices rise - both of which are comÂmon ocÂcurÂrences in the life of Doña Rosa AnÂgulo, a woman livÂing in the southÂern zone of the city of Cochabamba, BoÂlivia. This southÂern zone is what is known as a 'peri-urÂban' area, and within it is sitÂuÂated the comÂmuÂnity of Maria AuxÂilÂiÂadora, where Rosa lives.

This comÂmuÂnity was esÂtabÂlished for women. Only women own the land and only women can hold the poÂsiÂtions of presÂiÂdent and vice presÂiÂdent. A process inÂvolvÂing the enÂtire comÂmuÂnity has been esÂtabÂlished to deal with any doÂmesÂtic viÂoÂlence. It is a place where many women have found safety and supÂport.

My colÂleague Leny and I spent three months visÂitÂing memÂbers of the Maria AuxÂilÂiÂadora comÂmuÂnity and learnÂing about these women’s reÂsilience to chalÂlenges in their daily lives. The proÂject 'CliÂmate Change is About.. Women' seeks to show the reÂlaÂtions beÂtween this reÂsilience and the global chalÂlenge of cliÂmate change, inÂcludÂing the disÂproÂporÂtionÂate imÂpact it has on women.

CliÂmate Change and DisÂproÂporÂtionÂate ImÂpacts

In 2013 the InÂterÂgovÂernÂmenÂtal Panel on CliÂmate Change (IPCC) desÂigÂnated cliÂmate change as a threat to huÂman seÂcuÂrity for the first time. HowÂever, we are not all imÂpacted equally. The IPCC reÂport states that 'peoÂple who are soÂcially, ecoÂnomÂiÂcally, culÂturÂally, poÂlitÂiÂcally, inÂstiÂtuÂtionÂally or othÂerÂwise marÂginÂalÂized are esÂpeÂcially vulÂnerÂaÂble to cliÂmate change.'1 Those who have done the least to cause cliÂmate change sufÂfer disÂproÂporÂtionÂately from its efÂfects.

How we have conÂtributed to and are afÂfected by the planÂeÂtary criÂsis difÂfers deÂpendÂing on where we live. Those livÂing in the global North are not imÂpacted to the same deÂgree as those livÂing more vulÂnerÂaÂbly in the global South, nor have those from the ‘deÂvelÂopÂing’ world conÂtributed to the criÂsis anyÂthing like as much as govÂernÂments, inÂdusÂtries and popÂuÂlaÂtions in rich counÂtries. MitÂiÂgaÂtion, adapÂtaÂtion, and reÂsilience have difÂferÂent meanÂings in the global North than in the global South. While we all have reÂsponÂsiÂbilÂiÂties when it comes to the curÂrent criÂsis, our reÂsponÂsiÂbilÂiÂties do difÂfer deÂpendÂing on where we are based.

In the global North we must think about adapÂtaÂtion, but not at the exÂpense of mitÂiÂgaÂtion efÂforts or conÂsidÂerÂaÂtion of the hisÂtorÂiÂcal inÂjusÂtices that have deÂfined the dyÂnamÂics beÂtween the rich and poor arÂeas of the globe. InÂhabÂiÂtants and govÂernÂments of wealthy counÂtries need to foÂcus on mitÂiÂgaÂtion first and foreÂmost, and on adÂdressÂing unÂsusÂtainÂable, highly enÂergy-inÂtenÂsive lifestyles. The apÂproach to "deÂvelÂopÂment" of poorer naÂtions likeÂwise needs to have susÂtainÂabilÂity and jusÂtice at its core. Just one exÂamÂple would be adÂdressÂing the deÂforÂestaÂtion of large swaths of the AmaÂzon for agroinÂdusÂtry. The South has a lot to ofÂfer in terms of learnÂing about alÂterÂnaÂtive deÂvelÂopÂment, ways of livÂing, adapÂtaÂtion and reÂsilience. The North also has a lot it needs to ofÂfer in terms of techÂnolÂogy and knowlÂedge transÂfer around both susÂtainÂable inÂfraÂstrucÂture and adapÂtaÂtion asÂsisÂtance. But once again, acÂknowlÂedgÂing and meetÂing these reÂsponÂsiÂbilÂiÂties must not disÂtract from a foÂcus on mitÂiÂgaÂtion and overÂall emisÂsions reÂducÂtion. Rich counÂtries must not be alÂlowed to use SouthÂern 'reÂsilience' or small handÂouts of adapÂtaÂtion aid money as an exÂcuse for carÂryÂing on with busiÂness-as-usual.

BoÂlivia

ReÂsearch by OxÂfam states that beÂcause of the comÂbiÂnaÂtion of its geÂoÂgraphÂiÂcal loÂcaÂtion, diÂverse ecosysÂtems, exÂtreme poverty and inÂequalÂity, BoÂlivia is one of the most vulÂnerÂaÂble counÂtries imÂpacted by cliÂmate change.2 ‘In BoÂlivia... five main imÂpacts are preÂdicted to reÂsult from cliÂmate change: less food seÂcuÂrity; glacial reÂtreat afÂfectÂing waÂter availÂabilÂity; more freÂquent and more inÂtense ‘natÂural’ disÂasÂters; an inÂcrease in mosÂquito-borne disÂeases; and more forÂest fires.’3 This means a unique vulÂnerÂaÂbilÂity to cliÂmate change as well as limÂited (and, in some cases, dwinÂdling) reÂsources, such as waÂter, with which to conÂfront its preÂsent and fuÂture efÂfects – to adapt and be reÂsilient.

Peri-urÂban

One feaÂture of BoÂlivia’s fuÂture cliÂmate sceÂnario is masÂsive rural to urÂban miÂgraÂtion acÂcomÂpaÂnied by poverty, unÂemÂployÂment, and the unÂravÂelÂing of traÂdiÂtional soÂcial fabÂric.4 The 2013 IPCC reÂport also idenÂtiÂfied inÂcreased miÂgraÂtion as a fuÂture exÂpecÂtaÂtion of cliÂmate change imÂpacts on huÂman seÂcuÂrity.5 HowÂever, this is not a fuÂture cliÂmate sceÂnario. BoÂlivia is alÂready witÂnessÂing mass miÂgraÂtion to urÂban arÂeas, such as El Alto, the southÂern zone of Cochabamba, and Plan 3000 in Santa Cruz. In El Alto in-miÂgraÂtion has been so high that the popÂuÂlaÂtion of one milÂlion has surÂpassed that of the adÂjaÂcent city of La Paz, the poÂlitÂiÂcal capÂiÂtal of BoÂlivia.

This blurÂring of the rural and urÂban diÂchotomy is seen priÂmarÂily in the global South and the reÂsultÂing conurÂbaÂtions, ofÂten inÂforÂmal, have been inÂcreasÂingly reÂferred to as “peri-urÂban arÂeasâ€. Such arÂeas are poÂlitÂiÂcally marÂginÂalÂized and tend to lack necÂesÂsary serÂvices such as waÂter deÂlivÂery. A large secÂtion of the rapidly growÂing world popÂuÂlaÂtion is miÂgratÂing to these arÂeas, beÂing left exÂtremely vulÂnerÂaÂble to cliÂmate change imÂpacts and livÂing with unÂcerÂtain food, waÂter and other reÂsources.

Women

Within these peri-urÂban arÂeas it is also the case that not all are afÂfected by cliÂmate change equally. Women will be disÂproÂporÂtionÂately imÂpacted. The 2009 OxÂfam reÂport highÂlights that cliÂmate change imÂpacts in BoÂlivia will not be felt uniÂformly and that women, smallÂholder farmÂers and poor comÂmuÂniÂties will bear the brunt of this probÂlem, to which they did not conÂtribute.6

These women cook, clean the house, wash clothes, make sure there is food and waÂter, watch the kids, mainÂtain agriÂculÂtural land and many also work outÂside of the home - sellÂing what they can, sewing, cookÂing, nursÂing…Few have the time or money to study, much less earn a deÂgree and beÂgin a proÂfesÂsion. Many of these same women exÂpeÂriÂenced sexÂual viÂoÂlence as young girls and/or teenagers and go on to live with sexÂual and/or doÂmesÂtic viÂoÂlence as adults. Women have an unÂequal burÂden of reÂsponÂsiÂbilÂiÂties, less time availÂable, and exÂpeÂriÂence a greater amount of daily viÂoÂlence. It has also been emÂphaÂsized that women lack acÂcess to parÂticÂiÂpaÂtion in polÂicy and deÂciÂsion makÂing and that they have fewer inÂforÂmaÂtion reÂsources and less deÂciÂsion makÂing auÂthorÂity to cope with cliÂmate shocks and stresses.7 Women live the imÂpacts of cliÂmate change disÂtinctly - as anÂother form of viÂoÂlence in their lives, inÂterÂwoÂven with the rest; and they bear a larger burÂden of the viÂoÂlence than their male counÂterÂparts.

Yet most women forge on day afÂter day, thinkÂing of their chilÂdren: makÂing sure their belÂlies are full, that they are healthy, that they are goÂing to school. Women around the world are reÂsilient. Many are the rocks of their famÂiÂlies deÂspite the great amount of viÂoÂlence and opÂpresÂsion that they live with everyÂday. Some women - those that have the supÂport, reÂsources, strength and opÂporÂtuÂnity that they need - have more chances to get out of viÂoÂlent sitÂuÂaÂtions. It beÂcomes posÂsiÂble for them to take back conÂtrol of their lives, for themÂselves and for their chilÂdren.

Much of the cliÂmate change disÂcourse frames “…women as ‘vulÂnerÂaÂble, pasÂsive vicÂtims,…[which] reÂinÂforces [the] exÂcluÂsion of women as ‘acÂtive agents’ in reÂspondÂing to cliÂmate change and igÂnores their caÂpaÂbilÂiÂties, knowlÂedge and relÂeÂvant skills, which should be built upon in cliÂmate reÂsponses.â€8 The strength and reÂsilience of women, in diÂverse arÂeas of their lives, makes a woman’s viÂsion disÂtinct when it comes to conÂfronting the inÂcreasÂing difÂfiÂculÂties of cliÂmate change imÂpacts on, for exÂamÂple, their houseÂhold budÂgets and food seÂcuÂrity.

Women are not pasÂsive vicÂtims of viÂoÂlence or poÂlitÂiÂcal marÂginÂalÂizaÂtion and nor are they pasÂsive vicÂtims of the efÂfects of cliÂmate change on their lives. Women’s caÂpaÂbilÂiÂties, skills, and knowlÂedge are the diÂrect reÂsults of everyÂthing they have exÂpeÂriÂenced as chilÂdren, as wives and as priÂmary careÂtakÂers of their chilÂdren; as surÂvivors of sexÂual and doÂmesÂtic viÂoÂlence; and as those reÂsponÂsiÂble for proÂvidÂing food and waÂter. Their overÂall reÂsilience means that they are uniquely able to conÂfront the efÂfects of cliÂmate change in their homes and comÂmuÂniÂties.

HowÂever, it would be a furÂther inÂjusÂtice to rely solely on women to take this on. DoÂing so would add to the alÂready inÂequitable burÂden of reÂsponÂsiÂbilÂity - and poverty of time - that women bear. ReÂsponses to these imÂpacts should be colÂlecÂtive in naÂture, with inÂdiÂvidÂuÂals and comÂmuÂniÂties learnÂing from women’s disÂtinct abilÂiÂties and knowlÂedge in orÂder to reÂproÂduce the reÂsilience they demonÂstrate at the perÂsonal level in the broader soÂciÂetal efÂfort to conÂfront cliÂmate change.

And of course, reÂsilience does have a limit, esÂpeÂcially in exÂtreme conÂdiÂtions. While the caÂpacÂiÂties of women like those livÂing in Maria AuxÂilÂiÂadora to bounce back from shocks and sufÂferÂing is adÂmirable, in the end of course women should not have to be so reÂsilient: the unÂderÂlyÂing causes of those shocks and sufÂferÂing are sysÂtems of paÂtriÂarÂchal opÂpresÂsion which give soÂcial sancÂtion to viÂoÂlence against women as well as poverty and ecoÂnomic inÂequalÂity. These sysÂtems need to be chalÂlenged and taken apart. Women are not unÂbreakÂable, even if they are reÂsilient. WithÂout sysÂtemic threats to their wellÂbeÂing, all women could enÂjoy opÂporÂtuÂniÂties to flourÂish and deÂvelop themÂselves in other ways. What apÂplies at the perÂsonal level is also relÂeÂvant when we talk about cliÂmate reÂsilience. The strateÂgies that many women emÂploy in dealÂing with cliÂmate change in their daily lives at preÂsent may not serve them as their sitÂuÂaÂtions shift and the conÂseÂquences beÂcome more exÂtreme. But we also have to work to mitÂiÂgate against those more exÂtreme imÂpacts – which again means conÂfronting cliÂmate change and its inÂherÂent inÂjusÂtices at the sysÂtemic level. AdÂdressÂing cliÂmate change imÂpacts and viÂoÂlence against women go hand in hand.

Food

“Due to the fragÂile physÂioÂgraphic conÂdiÂtions of the counÂtry, the state of the land and waÂter reÂsources, and the preÂcarÂiÂous agriÂculÂtural sysÂtems, food seÂcuÂrity in [BoÂlivia] is highly vulÂnerÂaÂble to cliÂmate change efÂfects.â€9 This 2008 stateÂment reÂinÂforces the 2013 IPCC reÂport’s findÂing that one of the key threats that cliÂmate change repÂreÂsents is to our food. Crop yields need to inÂcrease to supÂport the growth of the global popÂuÂlaÂtion, but yields such as wheat and corn have slowed over the last 40 years. The reÂport shares the exÂpecÂtaÂtion of us seeÂing inÂcreasÂing food shortÂages and risÂing food prices over the next half-cenÂtury.10

“The main way that most peoÂple will exÂpeÂriÂence cliÂmate change is through the imÂpact on food: the food they eat, the price they pay for it, and the availÂabilÂity and choice that they have,†says Tim Gore, head of food polÂicy and cliÂmate change for OxÂfam.11 This will be exÂpeÂriÂenced more acutely by those livÂing in peri-urÂban arÂeas and by women, who are genÂerÂally reÂsponÂsiÂble for proÂvidÂing food and waÂter for the famÂily. Rosa AnÂgulo and her famÂily live in the southÂern zone of Cochabamba and she reÂmemÂbers how 2 boÂliÂvianos (apÂprox US¢30) used to buy 25 baÂnanas and 7 boÂliÂvianos used to buy 3 kiÂlos of onion; now the price of 25 baÂnanas flucÂtuÂates beÂtween 5 and 10 boÂliÂvianos and you need 14 boÂliÂvianos to buy that amount of onion. A 2010 study by the Women’s EnÂviÂronÂmenÂtal NetÂwork says that women in poor comÂmuÂniÂties, as a reÂsult of cliÂmate change imÂpacts, are more likely to “exÂpeÂriÂence inÂcreased burÂdens of waÂter and fuel colÂlecÂtion, feel the efÂfects of risÂing food prices most acutely, and be the first to sufÂfer durÂing food shortÂages…[as well as] be exÂpected to, and need to, adapt to the efÂfects of cliÂmate change, inÂcreasÂing their workÂload.â€12

Women in BoÂlivia like Rosa AnÂgulo are alÂready exÂpeÂriÂencÂing both food shortÂages and food price inÂcreases as a reÂsult of cliÂmate change imÂpacts. With agriÂculÂtural proÂducÂers losÂing an inÂcreasÂing numÂber of crops due to efÂfects such as changed plantÂing schedÂules and heavy and deÂstrucÂtive floods in the Beni reÂgion, less vegÂetaÂbles and fruits are arÂrivÂing in Cochabamba. More widely felt is the imÂpact on inÂcreasÂing food prices. 2013 world food prices were the third highÂest they’ve ever been13 and a UK reÂport by the InÂstiÂtute of DeÂvelÂopÂment StudÂies preÂdicts a 20-60% rise in food prices by 2050. MeanÂwhile 2012 was the secÂond to worst, and 2011 the worst year so far, for inÂflated food costs.4 This demonÂstrates a trend of inÂcreasÂing criÂsis which is only set to worsen in the face of an ever more unÂpreÂdictable cliÂmate. Those most vulÂnerÂaÂble, esÂpeÂcially women, will be facÂing the brunt of this. AdÂdiÂtionÂally, inÂtenÂsive inÂdusÂtrial farmÂing and exÂtracÂtive inÂdusÂtries will be pushed more heavÂily onto deÂvelÂopÂing economies - when susÂtainÂable food sovÂerÂeignty should be a main foÂcus and purÂsuit.

ConÂcluÂsion

Doña Irene CarÂdozo has put her famÂily’s qualÂity of life at the cenÂter of her daily deÂciÂsion-makÂing. LivÂing in the comÂmuÂnity of Maria AuxÂilÂiÂadora she is the owner of her own home - which she built herÂself - proÂvidÂing a seÂcure, staÂble, and safe place to live for herÂself and her two daughÂters. BeÂlongÂing to the comÂmuÂnity and ownÂing her own home supÂported Irene in getÂting away from doÂmesÂtic viÂoÂlence, and they proÂvide the place where she can plant trees and vegÂetaÂbles so that she and her daughÂters have a seÂcure fresh food source free from pesÂtiÂcides, preserÂvÂaÂtives and chemÂiÂcals. This is a huge help to them, parÂticÂuÂlarly as vegÂetable prices conÂtinue to rise in the marÂket, which is close to an hour’s bus ride away.

Back at Doña Rosa’s kitchen table, we sat down to eat a soup she had preÂpared with her deÂhyÂdrated vegÂetaÂbles and which she shared with us for lunch. Around the world women are strivÂing to proÂvide healthy food and a seÂcure enÂviÂronÂment for their chilÂdren, to enÂable them to thrive.

The changes in cliÂmate afÂfect the abilÂity to acÂcomÂplish this. It is beÂcomÂing harder to be reÂsilient beÂcause we are faced with more chalÂlenges – some, of course, much, much more so than othÂers. Yet for the women we spent sevÂeral months visÂitÂing in Maria AuxÂilÂiÂadora, the imÂpacts they are feelÂing from cliÂmate change are just anÂother chalÂlenge in a vast sea of viÂoÂlence they have been enÂcounÂterÂing their whole lives. The ways in which they are each reÂsilient are inÂspirÂing.